2021 FSA Posters

P017: DRUG-INDUCED METHEMOGLOBINEMIA AFTER RECENT HIGH-ALTITUDE TRAVEL: A CASE REPORT

Taimoor A Khan, MD1; Walter Diaz, MD2; Xiwen Zheng, MD2; Jennifer Pollak, MD1; Benjamin Houseman, MD, PhD, FASA2; 1Memorial Healthcare System; 2Envision Physician Services

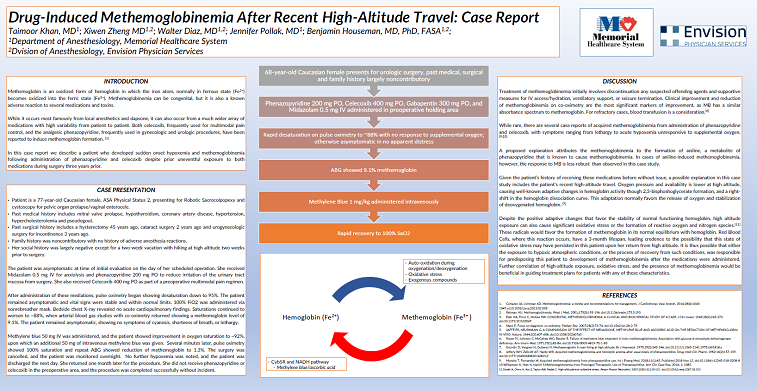

Introduction: Methemoglobinemia is a rare condition in which hemoglobin’s iron atom becomes oxidized and binds oxygen less effectively. Methemoglobinemia can be congenital or acquired; the acquired form typically occurs following exposure to medications or toxins that promote oxidation of heme iron. Here we report an unusual case of drug-induced methemoglobinemia in a patient with recent high altitude travel.

Case Report: A 77-year-old Caucasian female presented for robot-assisted sacrocolpopexy and cystoscopy. Past medical history was significant for mitral valve prolapse, hypothyroidism, coronary artery disease, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia and pseudogout. Past surgical history was significant for urogynecologic surgery under general anesthesia two years prior, during which she received both celecoxib and phenazopyridine. Two weeks before the day of this upcoming surgery, she had spent two weeks hiking at high altitude.

In the preoperative area, the patient received Midazolam (0.5 mg IV) for anxiolysis and phenazopyridine (200 mg PO) to reduce irritation of the urinary tract mucosa from surgery. She also received Celecoxib (400 mg PO) as part of a preoperative multimodal pain regimen. Five minutes after administration of these medications, pulse oximetry on room air decreased to 88%. Physical exam did not demonstrate any cyanosis, tachypnea, tachycardia, altered mental status, or lethargy. Supplemental oxygen was administered with no improvement in saturation. Chest X-ray was negative, and an arterial blood gas study with co-oximetry showed a methemoglobin level of 9.1%.

Methylene blue 50 mg IV was administered, and the patient showed improvement in oxygen saturation to 93%, upon which a second dose of methylene blue 50 mg IV was given. Her saturations improved to baseline and a repeat ABG showed a methemoglobin level of 1.3%. No further hypoxemia or symptoms were noted, and the patient was discharged home the next day. She returned for surgery three weeks later. She did not receive phenazopyridine or celecoxib and completed the procedure uneventfully.

Discussion: Both endogenous and exogenous factors can favor the formation of methemoglobin. This patient received both celecoxib and phenazopyridine, which have been shown to induce methemoglobin formation in the literature. However, she had received both medications before prior urogynecologic surgery without the development of clinically significant methemoglobinemia, and she had no other significant changes in her medical history except recent high altitude travel.

We suspect that oxidative stress from high altitude exposure contributed to development of methemoglobinemia following administration of celecoxib or phenazopyridine. Hemoglobin-methemoglobin equilibrium occurs in erythrocytes, which have a 3-month lifespan, and it is possible that either hypoxic atmospheric conditions or the process of recovery from such conditions predisposed her to the formation of methemoglobin. Since both celecoxib and phenazopyridine were given in this case (or not given in her subsequent visit three weeks later), it is impossible to determine which agent precipitated this event. Further correlation of high-altitude exposure, oxidative stress, and the presence of methemoglobinemia would be beneficial in guiding treatment plans for patients with any of these characteristics.